But Who Will Build The Roads?by Caleb McMillanNov. 06, 2012 |

Popular

Schumer Moves to Silence Criticism of Israel as Hate Speech With 'Antisemitism Awareness Act'

As Poll Finds Ukrainians Want to End War, U.S. Pushes Zelensky to Bomb Russia and Expand Conscription

FBI Pays Visit to Pro-Palestine Journalist Alison Weir's Home

Federal Judge Orders Hearing Into Questionable 'Auction' of Infowars to The Onion

'More Winning!' Ben Shapiro Celebrates Trump Assembling an Israel First Cabinet

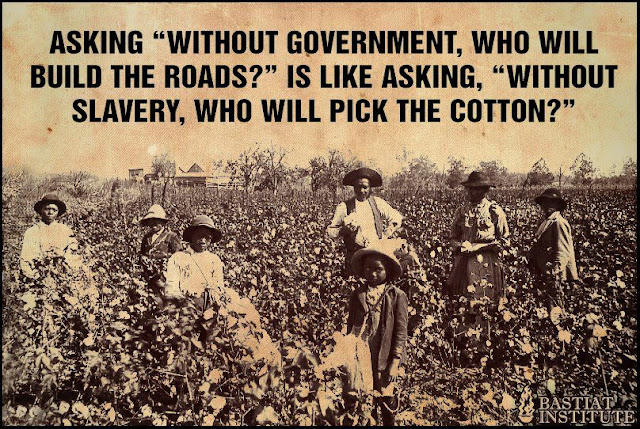

One of my favourite movies is Mike Judge’s Office Space. For those who haven’t seen it, I won’t spoil anything. The only reason I bring it up is because there’s a scene where a character named Tom Smykowski is, essentially, being interviewed for the job he already has. It seems that Tom’s job consists of being a middle man between customers and engineers. Here’s a sample of the scene. Somebody has created a meme for this scene, replacing the customer with the tax-payer and Tom’s role with the government.  In the spirit of this meme, I’d like to address the idea that somehow the “private sector” is unable to build the roads, airports, bridges, sewers, dams, ports, nuclear power plants and all the other “essential” services the state has monopolized. Really think about this argument for a moment. Millions of individuals associating with each other are unable to coordinate a plan to lay down slabs of pavement connecting point a with point b. No, individuals acting as entrepreneurs cannot exchange with each other to accommodate consumer interests. The process of creating a road requires a territorial monopoly that forces money from the general public. This monopoly must then pick and choose which construction companies will build the roads, the quantity of roads and the whereabouts of these roads. Clearly, and I’m being sarcastic here, slabs of pavement or gravel paths cannot be left to the whims of voluntary association and exchange. A system predicated on violence is required. Perhaps insufficient capital is the problem? For this is the common argument I hear: the benefit of forced payment is that it allows for a large accumulation of capital impossible under a free system of competitive entrepreneurs. But this argument rests on two fallacies. One being the obvious notion that government capital is an oxymoron. Capital indicates there was some sort of saving on the part of the individual or group. Capital forms when consumption is restricted; there are no “savings” within government. There cannot be any real “government capital,” as the government only taxes and spends. Even if the government merely “collects” and doesn’t spend the loot, this is no more capital accumulation than a thief that robs a bank and then stuffs the money under his mattress instead of immediately consuming it. The second fallacy regarding the argument that the private sector lacks the appropriate capital to finance projects such as roads, is the belief in homogeneous capital. This is popular among Keynesians, but it is in stark contrast to reality. Capital is an intricate complex order of goods interlocked in complementary structures. For one to say that business, whether large or small, lack the sufficient capital to build roads (or etc.) is a pretense of knowledge. Who’s to say how much or what kind of capital is required for roads? In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Hayek said, Unlike the position that exists in the physical sciences, in economics and other disciplines that deal with essentially complex phenomena, the aspects of the events to be accounted for about which we can get quantitative data are necessarily limited and may not include the important ones. While in the physical sciences it is generally assumed, probably with good reason, that any important factor which determines the observed events will itself be directly observable and measurable, in the study of such complex phenomena as the market, which depend on the actions of many individuals, all the circumstances which will determine the outcome of a process, for reasons which I shall explain later, will hardly ever be fully known or measurable.Millions of individuals with subjective preferences exchange with each other and by doing so, an objective price mechanism arises. Entrepreneurs use this price mechanism to determine how best to allocate scarce resources to meet consumer demand. Competition among entrepreneurs weeds out the ineffective thus awarding the consumer with efficiency. This process, known as the free market, has created a standard of living unimaginable for even the wealthiest of centuries past. This process changed computers from large expensive glorified calculators to small hand-held devices affordable to virtually everyone. The market process created a world where food comes all in varieties and in abundance for a low price. Contrast this to the development of computers and grocery stores in societies where the state owned the means of production. State ownership in roads and other “essentials” retard the technological development inherent in the free market. When asked, “who will build the roads?” I’m often inclined to say, “I don’t know.” This usually creates a sense of triumph in the opposing party, that the admission of “I don’t know” confirms their suspicion that the market is inferior to state coercion. But “I don’t know” isn’t an admission of defeat, but rather, an admission that I can’t predict the market process. I was eight years old when my family got our first computer; I remember it clearly but in no way could I have predicted what the future of computers would hold. The same is true for roads and other infrastructure thought only to be capable by a territorial monopoly. I can’t predict what roads would look like or how they would function without the government’s monotonous slabs of pavement. And even if I could, that would be a case for state planning, for if I could envision the future, why not a council of bureaucrats with allocated funds extracted from the populace? Again, Hayek perfectly describes the dilemma at hand, If man is not to do more harm than good in his efforts to improve the social order, he will have to learn that in this, as in all other fields where essential complexity of an organized kind prevails, he cannot acquire the full knowledge which would make mastery of the events possible. He will therefore have to use what knowledge he can achieve, not to shape the results as the craftsman shapes his handiwork, but rather to cultivate a growth by providing the appropriate environment, in the manner in which the gardener does this for his plants. … The recognition of the insuperable limits to his knowledge ought indeed to teach the student of society a lesson of humility which should guard him against becoming an accomplice in men’s fatal striving to control society -- a striving which makes him not only a tyrant over his fellows, but which may well make him the destroyer of a civilization which no brain has designed but which has grown from the free efforts of millions of individuals.Murray Rothbard envisioned a system of privately-owned roads, as has Walter Block. Tom DiLorenz has written about the myth that “essential” goods and services must be monopolized. I won’t repeat their conclusions here. Instead, I’ll leave you with another meme. One that I have used to prevent long-winded political debates with statists:  _ Caleb McMillan is an autodidact and an aspiring polymath. He’s travelled all over Canada and currently resides in Canmore, Alberta where he works at a Canadian Tire. He blogs at TANSTAAFL CANADA! |